- Military to replace leading firefighting tool used since Vietnam

- Airports, oil, chemical industries also bracing for change

Kevin Ferrara spent his career working around a wispy white chemical foam that could douse the hottest jet-fuel fires he fought, and was still considered harmless.

“Just like soap and water,” Air Force officials said of the firefighting foam Ferrara’s teams relied on, trained with, waded through, and even sprayed around giggling kids during the base’s annual Fire Prevention Week. “We believed it.”

Decades later, the former Air Force firefighter has diabetes, elevated cholesterol, and higher-than-average per- and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) chemicals in his blood. And the Pentagon knows the PFAS-based foam he worked with had a noxious side.

In January, it will unveil specifications for a PFAS-free replacement. By next October all new foam the military buys must meet those specs, and a year later the Defense Department must cease all PFAS-based foam use.

It’s a radical change for the US military, which since Vietnam has relied on PFAS-laden aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) to fight its toughest fires. And the process of switching to a safe and effective replacement will cascade through the nation’s civilian airports, fire departments, oil refineries, and chemical makers.

“We are staring at the tidal wave of foam transition,” said Corey Theriault, principal water engineer with Arcadis NV, which has helped US and international public and private sectors switch to firefighting foams without PFAS.

‘Lifesaving Material’

The Navy and the 3M Co. invented AFFF after the 1967 fire aboard the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal off the coast of Vietnam killed 134 sailors. Within a few years AFFF was used on all aircraft carriers, and soon throughout the military and civilian airports and firehouses.

AFFF works so well because it takes only seconds to extinguish diesel, propane, gasoline, and jet fuel fires. A small amount of a PFAS solution combined with lots of water foams up and smothers the flames.

“It is a lifesaving material,” said Ray Frigon, an assistant director in Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

Kevin Ferrara (off camera) teaches aircraft rescue firefighting tactics at the Ramstein Air Base, Germany, in 2006.Photo: Courtesy of Kevin Ferrara

But a half century of use also has threatened lives, polluting water supplies and the environment.

3M withheld from the Environmental Protection Agency for years more than 1,000 studies that showed health effects of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), one of the PFAS used in AFFF, a federal court said Sept. 16 in a mass tort litigation case involving the firefighting foam.

Yet the company shared other information that, by 1981, led the EPA to conclude PFAS could remain in human blood for years. Some of the chemicals can break down into substances that remain in the environment and get into plants, animals, and people—even babies, who get PFAS through breast milk.

By 2001, the agency knew the chemicals were turning up all over the world. In 2002, under pressure from the EPA, 3M stopped making an entire line of PFAS, including those used in firefighting foams.

But other chemical and foam manufacturers stepped in with AFFF formulations containing new types of PFAS—foams that the government and private sector still use.

Forever Chemicals

AFFF is among the biggest sources of PFAS pollution. Unlike other products it’s designed to be sprayed into the environment, which has meant torrents of PFAS-containing foam flushed directly into streams and rivers and off ship decks into the ocean.

The Pentagon spent more than $1.1 billion by 2020 to treat contaminated water, provide bottled water, and investigate pollution at nearly 700 military installations that have AFFF contamination. “Future PFAS costs will total at least $2.1 billion (and likely much more),” the Government Accountability Office said in a report.

That year, Congress ordered the Defense Department to stop training firefighters with AFFF. The Federal Aviation Administration followed by telling about 500 large airports that require use of the foam that they need do so only for emergencies.

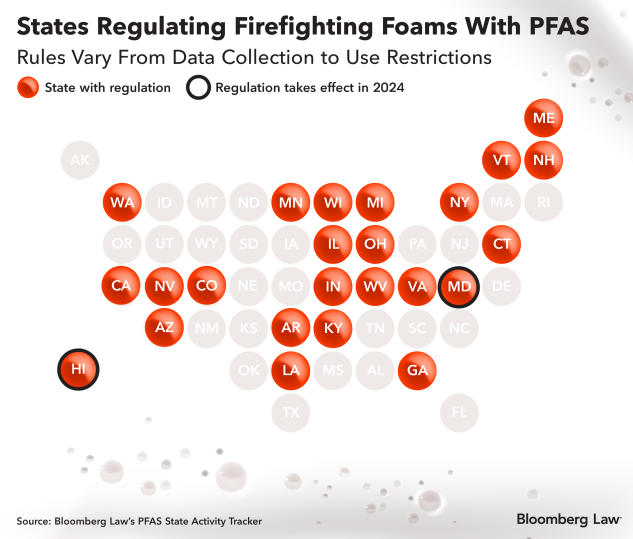

Twenty-four states also now ban training with AFFF or otherwise restrict its use.

The Pentagon continues to use AFFF for now “because it is the only current product that can quickly extinguish these types of fires and keep them out to protect the lives of our service men and women, our firefighting personnel, and others being rescued in emergencies,” says a DOD website. The FAA reached similar conclusions.

Once the military makes the switch, cleanup will take time. The Pentagon has 2.5 million gallons of AFFF in service and 500,000 gallons in reserve that it must manage or destroy, while also cleaning out more than 3,000 firefighting trucks and other vehicles, and more than 1,500 aircraft hangers and other buildings, it told Congress last year.

What’s more, disposal costs and potential liability could increase for the military and others with old AFFF if the EPA finalizes a proposed plan to declare PFOA and PFOS hazardous substances under the Superfund program.

‘Coordinated National Plan’

“Industry recognizes a need to transition to a fluorine-free foam,” said Justin Barkowski, vice president with the American Association of Airport Executives. The question is, “how do we get from Point A to Point B?”

The Pentagon has reviewed alternatives from AFFF manufacturers National Foam, Angus Fire, and Perimeter Solutions—which now make PFAS-free foams certified to meet International Civil Aviation Organization standards—and GreenFire, which was founded in 2016 to produce products free of carcinogenic ingredients including PFAS.

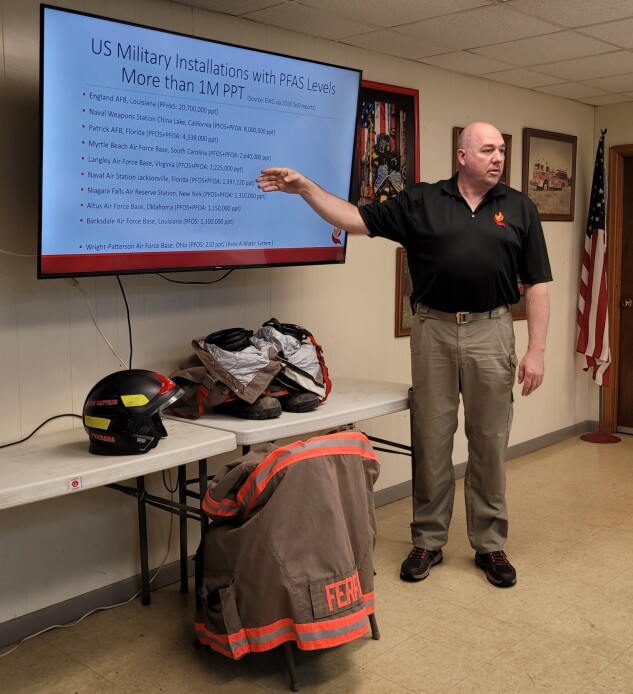

Former Air Force firefighter Kevin Ferrara, now a consultant specializing in PFAS, talks at the Woolrich Volunteer Fire Company in Woolrich, Pa., in 2022.Photo: Courtesy of Kevin Ferrara

Port of Seattle Fire Chief Randy Krause, who oversees the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and serves on a committee working with FAA staff on the foam transition, said the FAA is expected to adopt the foams the military approves.

He’s budgeting hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase new foams and hire specialists to carefully clean out equipment so the new foams don’t get contaminated with PFAS.

But, “we need a coordinated national plan” to make sure airports get the new foam, new equipment when necessary, and access to equipment cleanup specialists and technologies, Krause said.

The FAA would be directed to work with the DOD and help airports transition to the new types of foam in the appropriations bill report that accompanies the consolidated appropriations bill, H.R. 8294, the House passed July 20, and the report language Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) released July 28.

Similar language in both chambers increases the likelihood that it will be part of whatever final omnibus bill and report they agree to, said Andrew Pantino, AAAE’s vice president for government affairs.

Airports

The FAA controls aspects of air travel and safety, including firefighting foams at major airports.

Yet states also have authority.

“Some states have passed legislation requiring that once the [Pentagon’s] milspec is approved [in January], airports will have to make the transition within a very limited time frame—perhaps only a few months,” said Jeffrey Longsworth, a trial attorney and adviser on environmental laws and regulations at Barnes & Thornburg LLP.

Many airports won’t be able to meet the deadlines, said Longsworth, who counsels the PFAS Regulatory Coalition representing airports and other industries. “You can’t just substitute one foam for another,” he said. “You have to clean equipment. You may have to purchase new nozzles.”

“PFAS is a sticky thing,” said Richard Spiese, who works on waste issues at Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources, and co-chaired a team of state officials that developed AFFF guidance. “It wants to stay on the side of the equipment, the rubber or whatever, so it’s really hard to get out.”

Cleaning firefighting equipment generates its own PFAS-contaminated wastewater that has to be managed, said Frigon, who has overseen Connecticut’s pilot projects cleaning out AFFF from firetrucks.

So cleanup can be expensive, and perhaps not even an option, Longsworth said.

“If, as a hypothetical example, it will cost $600,000 to adequately clean a fire truck and $800,000 to get a new one, they’ll have to make a decision,” he said. “And it’s not like all the foam you need will be available even to purchase, if you could, right away.”

While it’s unclear how long some airports, oil refineries, chemical manufacturers, and local fire departments will keep using AFFF foams in states that allow it, most understand the need to follow the Pentagon’s lead, said Cynthia AM Stroman, an environmental practice partner with King & Spalding LLP.

“It’s not a matter of if,” said Stroman, “it’s a matter of when.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Pat Rizzuto in Washington at prizzuto@bloombergindustry.com; Andrew Wallender in Washington at awallender@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Renee Schoof at rschoof@bloombergindustry.com; Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com